Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Michael Cunningham is a very talented writer. Focusing on themes of love and death, regeneration and survival, 'Specimen Days' is a cleverly structured, well-written triptych. The three sections are linked by three recurring characters, while Walt Whitman's poetry provides a continuity throughout that supports the regeneration theme. In many ways, the book reminded me of David Mitchell's 'Cloud Atlas'; structurally, thematically, and in the writer's skillful narration from different perspectives.

Although the first section is set amid the grinding poverty of mid-nineteenth century immigrant New York, the second in contemporary fear-stricken New York, and the third in a dystopic future-New York, this book is - ironically - profoundly optimistic. The settings are interesting and believable, and the lives of the characters compelling.

A good read.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Written as if compiled from a variety of historical documents – diaries, letters, eye-witness accounts - this tells the story of a voyage from Ireland to America in 1847. The ship ‘Star of the Sea’, with 402 ½ steerage passengers, and 15 First Class passengers on board is the scene of mystery and murder. The tale is delivered to us some 70 years later by one of the First Class passengers, American journalist Grantley Dixon. How reliable is he as a narrator? How objective? That’s all part of the fun, really.

Most of the passengers are Irish fleeing starvation for the promise of plenty as Famine sweeps their homeland. O’Connor presents a fascinating, well-researched and beautifully written slice of history, drawing attention to the deprivations suffered by tenant farmers as they struggled to pay rents, the hardships of eviction, and the pain of hunger and disease. He humanises rich and poor, criminals, religious zealots, aristocrats and the law-abiding, as he describes life in the mid-nineteenth century. Detailed background of the main characters provides plenty of nourishment for the imagination and the intellect.

Completely absorbing, I really didn’t want to put this book down.

Friday, September 15, 2006

This book won the ’Bollinger Everyman Prize for Comic Fiction’ (whatever that is!), and I have to say it was very funny; made me laugh out loud.

But at the same time it was also very moving. Covering themes of family and memory, love, loneliness and survival – and tractors - the book follows the Mayakevsky family on a journey from Stalin to Thatcher and beyond.

It is the story of octogenarian widower Nikolai, his chalk & cheese daughters Nadia and Vera, and his outrageous young wife Valentyna.

Lewycka manages to poke fun at everyone in the book, but so gently and drily that I ended up liking all the characters, despite their all too human shortcomings. Or because of them.

A lovely book. 10 out of 10.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Dense, intense, a mountain of a book.

Describing 3 snowbound days in a remote Turkish town, this novel examines politics and religion in modern Turkey. Pamuk examines the uneasy relationship that exists between nationalism and Islam, and the conflict between a desire for prosperity & progress and the fear of a creeping Westernisation that threatens to undermine Islam and republicanism. Alongside this Pamuk sets Kurdish nationalism, and never lets the reader forget the legacies of Armenia, and Russian colonialism.

The novel is fascinating in its analysis of Islamic extremism, particularly the examination of women’s place in Islam and in Turkish society. Pamuk doesn’t flinch from allowing his characters, on all sides of the arguments, to express their opinions and their doubts. In the environment of restricted free speech that exists in Turkey, you can but admire his bravery.

I have to admit that reading this book was hard work, partly because the subject matter is so foreign to my liberal Western background, but also due to the intense prose style. But it is a book that merits close attention and is worth persevering with – you really need to read the whole thing to fully appreciate it.

Monday, September 04, 2006

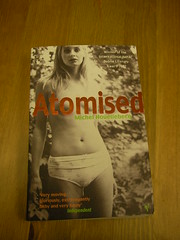

Atomised by Michel Houellebecq

Atomised by Michel Houellebecq

Originally uploaded by northern green pixie.

I found this to be a pretty bleak, depressing, and difficult novel to read. It is written from a perspective of 70 years or so in the future, looking back on the lives of two half-brothers through the second half of the 20th century. Both men struggle to establish meaningful relationships with their peers, especially with women, and with each other. Both have been brought up by a different grandmother,having been abandoned by their parents. Houellebecq uses their dysfunctionality to examine the society in which they live - post-religious, sexually liberal, materialist - and finds it greatly wanting. Discussing science and philosophy in this context, with frequent references to French culture, Houellebecq's fictional world was, to me, opaque and obscure. Much of it went right over my head. Houellebecq's futuristic premise is that early 21st century society undergoes a 'metaphysical mutation', entering into a Huxleyan brave new world, but one which, due to the sociological and scientific changes that have taken place since Brave New World was written, offers a genuine utopia, rather then the dystopia that Huxley envisaged. I can't decide whether this is intended to be ironic or not. Is Houellebecq suggesting that humanity will, after all, ignore Huxley's warning and go down the path of genetically manufacturing its future? He spends 350 pages discussing the hopelessness of love, and the destructiveness of desire, finally making both redundant. The novel, on the face of it, celebrates this redundancy, but is Houellebecq actually warning us that the alternative to our painful, emotional lives is a sterile, cloned existence, and inviting us to choose?? Perhaps.

This is a relentlessly masculine novel, and one that, though compelling, I really didn't enjoy.

Friday, September 01, 2006

I read Collins' book about growing up in the '70s - Where Did It All Go Right? - a couple of years ago, and really enjoyed it. He is just one year younger than I am, and from a similar background, so I could relate to a lot of his experiences and all his pop culture references. This book follows him through his student days at Chelsea College of Art and beyond during the 1980s. I didn't find it as funny as the earlier book, but still enjoyed it. I wasn't a student in the 80s but I did share a house for a while in North London with a young Barnsley woman who was in the same year at Chelsea as Collins, so in a sense (by proxy) mine & Collins' paths crossed. Sharon - the Barnsleyite - was a larger than life character, very tall, very loud. I remember coming home from work one day to find she had painted big blue elephants all over the bathroom, and she often woke me up at stupid o'clock on a Sunday morning with full-volume Prince. Sharon & Collins must have known each other, if only slightly, but I think they moved in different circles. Collins makes a couple of disparaging references to Lady Sarah Armstrong Jones, but I know she was a friend of the lovely Sharon.

My enjoyment of this book came largely, again, from familiarity with the pop culture of the time. There are clever uses of song lyrics of the time slipped in here and there, and Collins brings in contemporary politics (albeit very lightly) to contextualise & illustrate his own developing political awareness. I wonder if he was on the same demos as me?

Anyway, very much a book for people of a certain age, I think.